Exhibition: «shukir, zhaksy turamiz» Rashid Nurekeyev

Boar, paper, acrylic, 86 x 61 cm, 2010

“On my school notebooks

On my desk and on the trees

On the sands of snow

I write your name

On the pages I have read

On all the white pages

Stone, blood, paper or ash

I write your name

On the images of gold

On the weapons of the warriors

On the crown of the king

I write your name

[…]

On abstraction without desire

On naked solitude

On the marches of death

I write your name

And for the want of a word

I renew my life

For I was born to know you

To name you

Liberty.”

Paul Eluard, 1942

“shukir, zhaksy turamiz” (doing well, thanks goodness!)

Curated by Madina Sergazina

The painters and sculptors of contemporary art, formed in Kazakhstan in the 90s and 2000s, went through the same marginalization as Filippov or Kosolapov, however they did not have a stable infrastructure of galleries, patrons and spectators, which began to form in the mid-2000s in Russia. Over the past few years, the situation has changed: in the capital (TSE Art Destination, Hydra art factory), in Almaty (Tselinny, Esentai Gallery, Aspan Gallery, Art Future), abroad (Sapar Contemporary, Andakulova Gallery Dubai, IADA), as well as in the digital space (Qazart) - new institutions have been created that form a network of passionaries and professionals promoting Kazakhstani artists. However, despite the fact that the latter managed to earn recognition on the international art scene, the local audience is often not familiar with their works.

One of the main representatives of the older generation of Kazakhstan's contemporary art - Rashid Nurekeev, remains an artist that is not understood by everyone. Firstly, he is rarely exhibited and most of his paintings are in private collections. Secondly, Nurekeev expects an active position from the viewer: the ability to unleash a ZIP file consisting of visual and text components compactly bound together. “Traditional painting has ceased to respond to the challenges of modern culture” - Rashid’s statement that partly explains the variety of expressive tools of his artistic practice, which we tried to open through the exhibition «Шүкір, жақсы тұрамыз».

Rashid Nurekeev was born in 1964 in the village Zhusaly, near the city Kyzylorda. Recalling his childhood, the artist notes the role of his grandmother, who supported his ideas: she allowed him to cut out the pieces from newspapers and magazines for assemblages, and then to stick finished compositions on the walls. Whole new worlds were created: New York skyscrapers coexisted with exotic animals and intricate ornaments from other parts of the world. That is how the author’s attachment to the collage technique appeared, it can be an imitation of the latter on a large format canvas painted with acrylic: the surface seems to be assembled from several rags of different textures, although in fact it is absolutely smooth and homogeneous. So, for example, in the series «Не қарайсың?» (2010 Қазір түкірем, Кастеев, Шәмші Қалдаяков, Көті кім, Халк) the author, applies paint, varying the size and density of strokes. The faces of the protagonists and the background strongly contrast in color, a feeling of vibration is created, individual elements seem to protrude from the two-dimensional space of the painting.

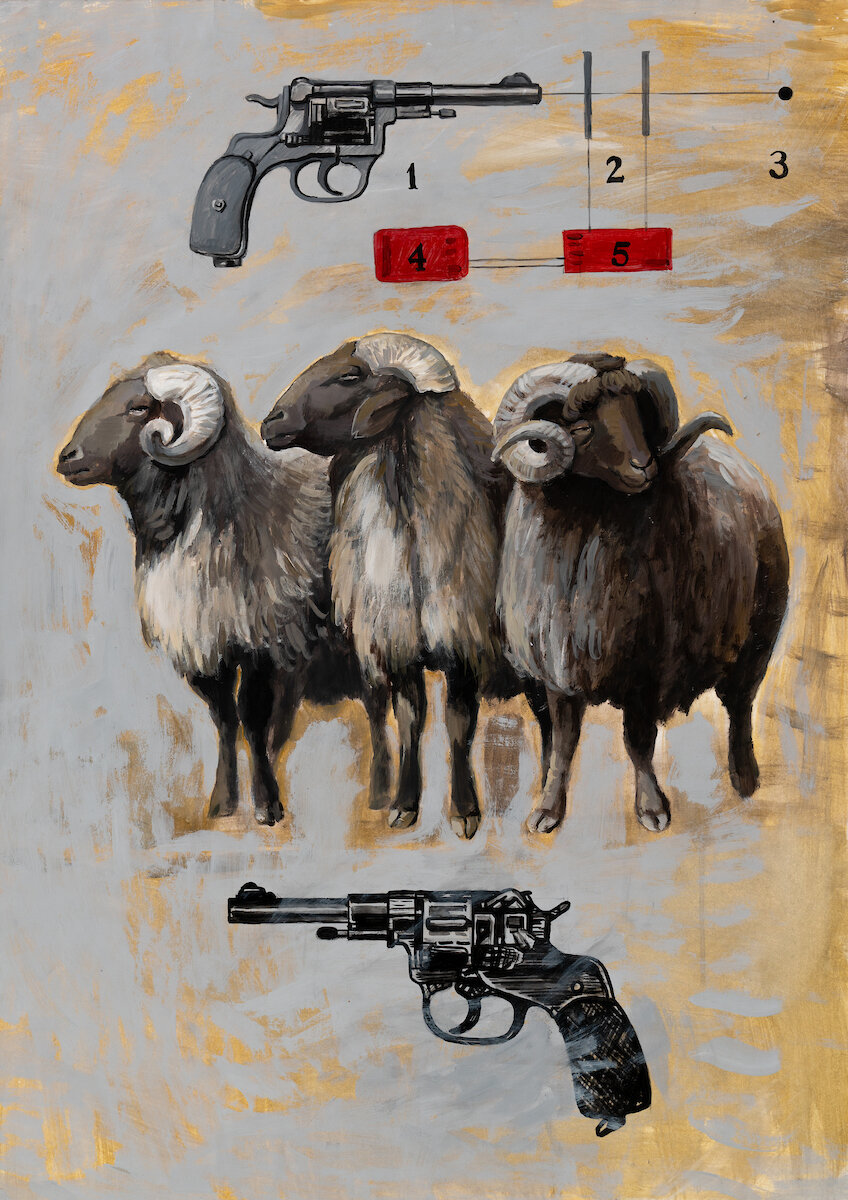

In other cases, the works are indeed created by combining non-obvious materials, as in the later series «Айтыс» (“aitys” - kazakh eloquence contest) (2013-2014), where instead of canvas there are sheets of tin. Aitys - a song contest between two improviser-poets, was once the mouthpiece of steppe democracy. Today this genre has degenerated, on poster clippings that Nurekeev glues on top of metal, the performers have no faces. A repulsive impression is constructed via several different means: on the semantic level, because you involuntarily feel disappointment and shame for your own inaction in the context of general lack of freedom, as well as on the physical level: you don’t want to approach the cold, unprocessed, tin plates with sharp edges and notches. In the series “Shooting dogs by aliens” (2013) and “Krylov's Fables” (2012), an unlikely support is also used: plywood and the walls of wooden boxes, respectively. In this case, the visual and semantic layers are also thoughtfully chosen: yellow and orange in the palette are traditionally associated with anxiety, which resonates with the plot.

No matter how far Rashid was led by the imaginary childhood wanderings he went on, picking up scissors and a couple of travel magazines, he always mentally returned back to Zhusaly, with its unpretentious joys and concerns. A riot of colors and air filled with special smells: freshly baked bread, mowed grass, flowering fruit trees. It seems to us that love for one’s native land is made up of these kinds of insignificant impressions and memories.

Patriot (from the Greek πατριώτη) - "fellow countryman, compatriot", "a man who loves his country, land, people." The word is so familiar that its meaning seems unambiguous. But it is also true that this word has acquired many new shades and connotations, and, to some extent, has become an anachronism. In a world where there is a merger of different, moreover, often, paradoxically, mutually exclusive cultures, it is becoming increasingly difficult to determine your belonging to a particular group. Nevertheless, no matter what the object of this patriotic love is, the principle is always the same: If I love something - that means I want to make it better, that means I see the flaws and speak out loud about it, as in Abay's “Words of Edification”, who severely scourged the vices of the Kazakhs, suffering deeply from the fact that his native people indulge in laziness and idleness. In this sense, Rashid Nurekeev is a true patriot who sincerely worries about his country. Fearlessly looking at yourself implies an incredible sense of courage, maturity and continuous internal struggle. These experiences are reflected in his works, and as a red thread goes from series to series.

Sometimes the need to talk, in language of contemporary art, about things that are much broader and addressed to a much wider audience than, in fact, the problems of contemporary art, may put the artist in a difficult position. The majority chooses the simple way and creates poster-like pieces. For Rashid, such an approach is unacceptable. He never allows himself to use straightforward, rude utterances, instead he strives to find subtle visual images. As for his critical attitude towards Kazakhstani reality, Nurekeev cannot be considered a political activist, and he does not engage in an openly propagandizing art. Reflecting on the problems of the present, Rashid takes the position of an “ordinary person”, from birth, placed in a complex social structure consisting of laws and more informal beliefs. Growing up, the individual tries to form his own picture of the world. This process of self-identification is made possible by the Other.

We can allow ourselves to assume that the Soviet experiment, which took as its basis the unification of minds and ways of thinking, failed miserably, since it goes against human nature. To be different is a necessity, otherwise what is a “personality"? At the same time, in order to appreciate the benefits of such diversity, we need a culture of communication, skills of perception of other ways of thinking. Mind-broadening occurs through the acceptance of the distinct views in one’s system of representations. The main paradox is that the fuller the personality is, the more specific it becomes, and the more difficult it is for a narrow-minded person to accept and define it in one of the categories in which he or she thinks. It is hard to attribute Rashid to one or another artistic movement. Rather, one can distinguish a characteristic feature: the ability to combine allusions to various events, historical periods and motives of national folklore on one canvas, as in his graphic “Series” (2012), in which Yulia Sorokina sees “criminalist’s sketches reflecting the course of thoughts and their associative relationship.” (quote from the text “The modest charm of simulacra” by Rashid Nurekeev).

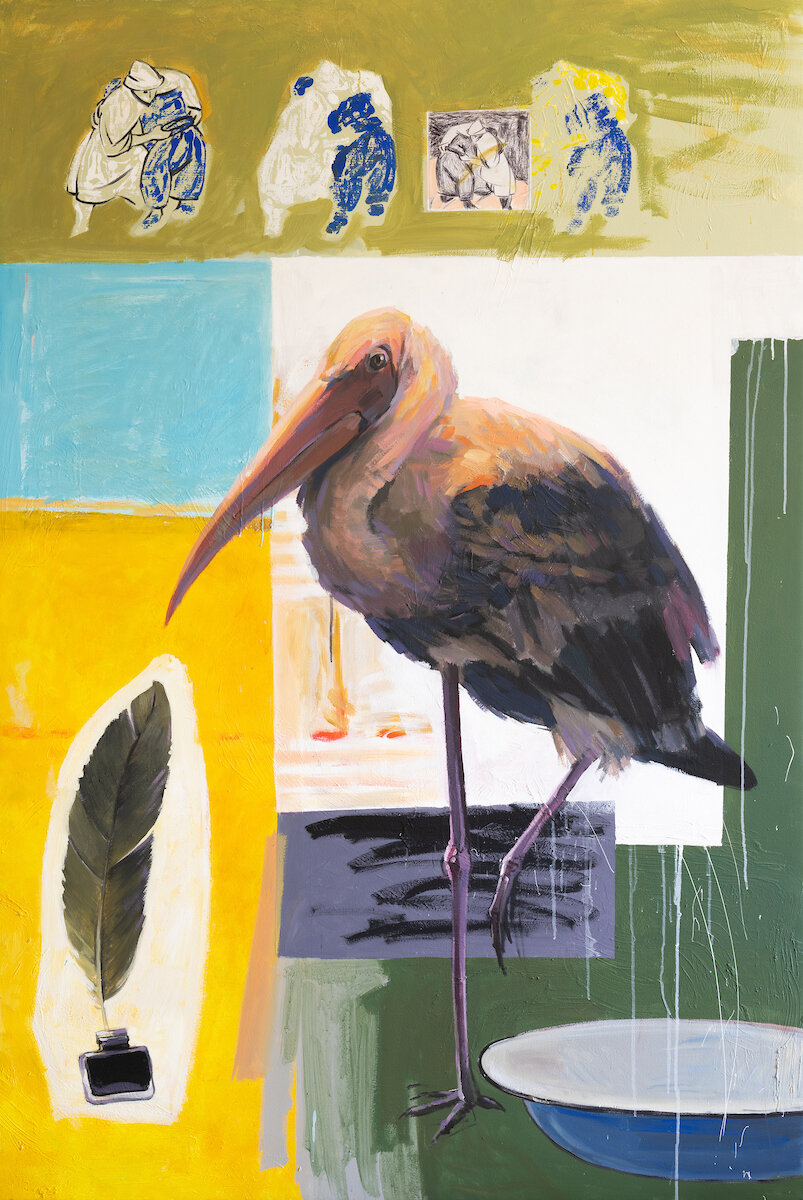

Animalistic metaphors also form a leitmotif. Introducing parallels with the animal world is his favorite technique. Within the framework of this exhibition, special attention is paid to birds. Crows distributed throughout the hall are real hunting decoys that fulfill their function: encourage the viewer to plunge into the exhibition space. The latter and feathered protagonists painted on canvases are disguised human characters living in a certain hierarchy. The comedy of Aristophanes “Birds” comes to mind. The Athenians Pisthetaerus and Euelpides, disappointed, leave their hometown in search of Tereus, the legendary Thracian king who was once metamorphosed into the hoopoe bird, to create a new, more perfect state on trees together. Most supported them, and they created their own city-in-the-sky, which they name “Cloud Cuckoo Land”, while also hijacking the smoke from the sacrifices, traditionally addressed to the gods who feed on them. Enraged by this insolence, the latter send an embassy to them. The head of the city comes to a peace agreement, and the birds who rebelled against “Cloud Cuckoo Land” democracy were served at a feast on this occasion. Rashid’s paintings speak of the same paradigm when those who decided to go against the established system of privileges were destined for the fate of martyrs.

Без названия, холст/акрил, 139 х 211 см, 2019

Wind in steppe, acrylic on canvas, 139 х 214 cm, 2019

Untitled, collage, 151 x 151 cm, 2019

Fox hat, mixed media, acrylic on canvas, 144 х 196 cm, 2019

Untitled, acrylic on paper, each 86 x 61 cm, 2012

Not a stork, acrylic on canvas, 297 x 139 cm, 2019

Untitled, 207 х 139 cm, canvas / acrylic, 2019

Untitled, acrylic on paper, each 86 x 61 cm, 2012

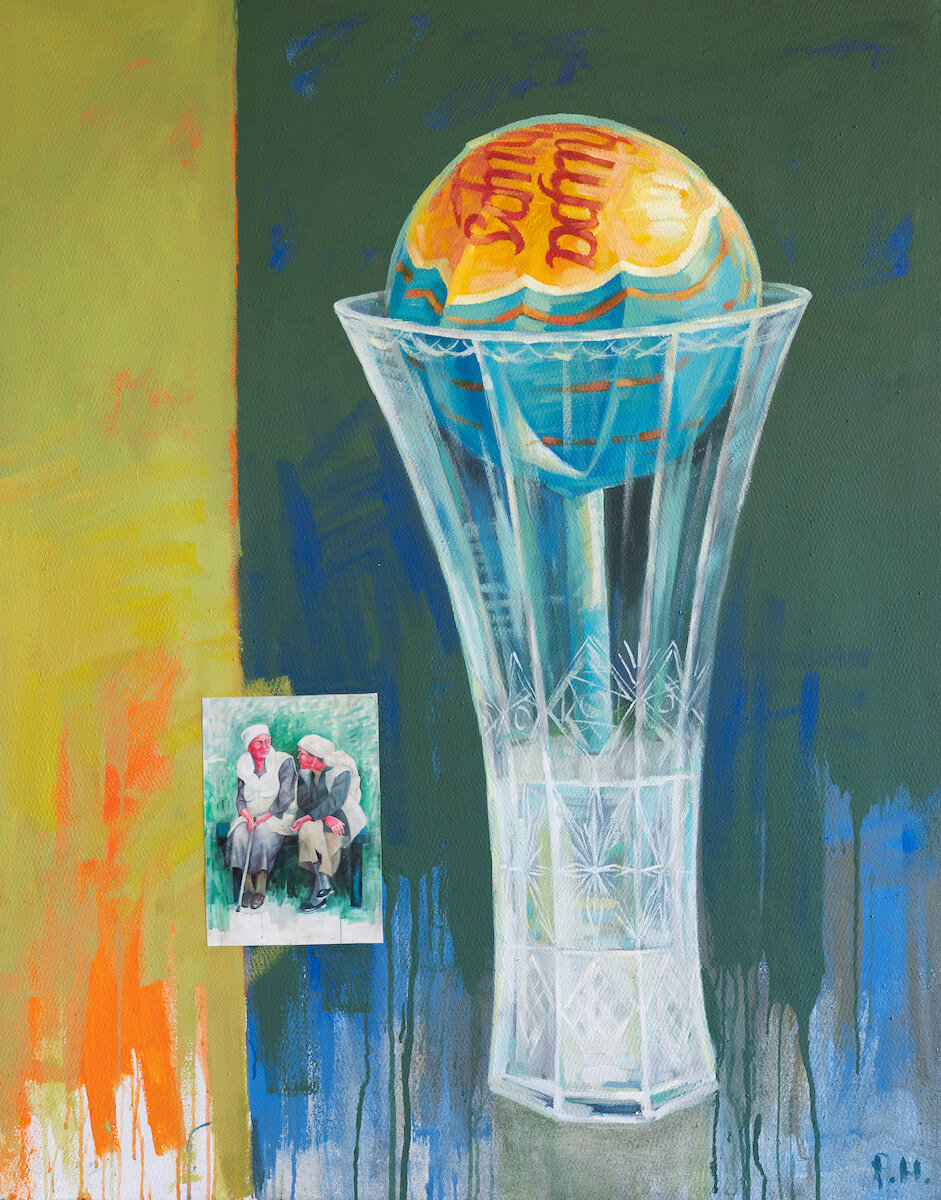

Lollipop, acrylic on canvas, 140 х 110 cm, 2020

Piano, canvas / acrylic, 150 x 170 cm (?), 2010

Fetching water, acrylic on canvas, 140 x 110 cm, 2020

Wheel, acrylic on canvas, 140 x 110 cm, 2020

Untitled, acrylic on paper, each 86 x 61 cm, 2012

Propane, acrylic on canvas, 207 х 139 cm, 2019

Tongue, acrylic/oil on canvas, 120 х 150 cm, 1999

Shooting dogs by aliens, photo-collage, plywood, acrylic, 122 x 81 cm, 2015

Untitled, acrylic on paper, each 86 x 61 cm, 2012

Weather vane, acrylic on canvas, 207 x 189 cm, 2019

Analgin, acrylic on paper, 60 х 80 cm, 2011

01 series, acrylic on paper, 60 х 80 cm, 2011

01 series, acrylic on paper, 60 х 80 cm, 2011

01 series, acrylic on paper, 60 х 80 cm, 2011

Untitled, acrylic on paper, each 86 x 61 cm, 2012