Falling in love: an interview with artist Katya Kan

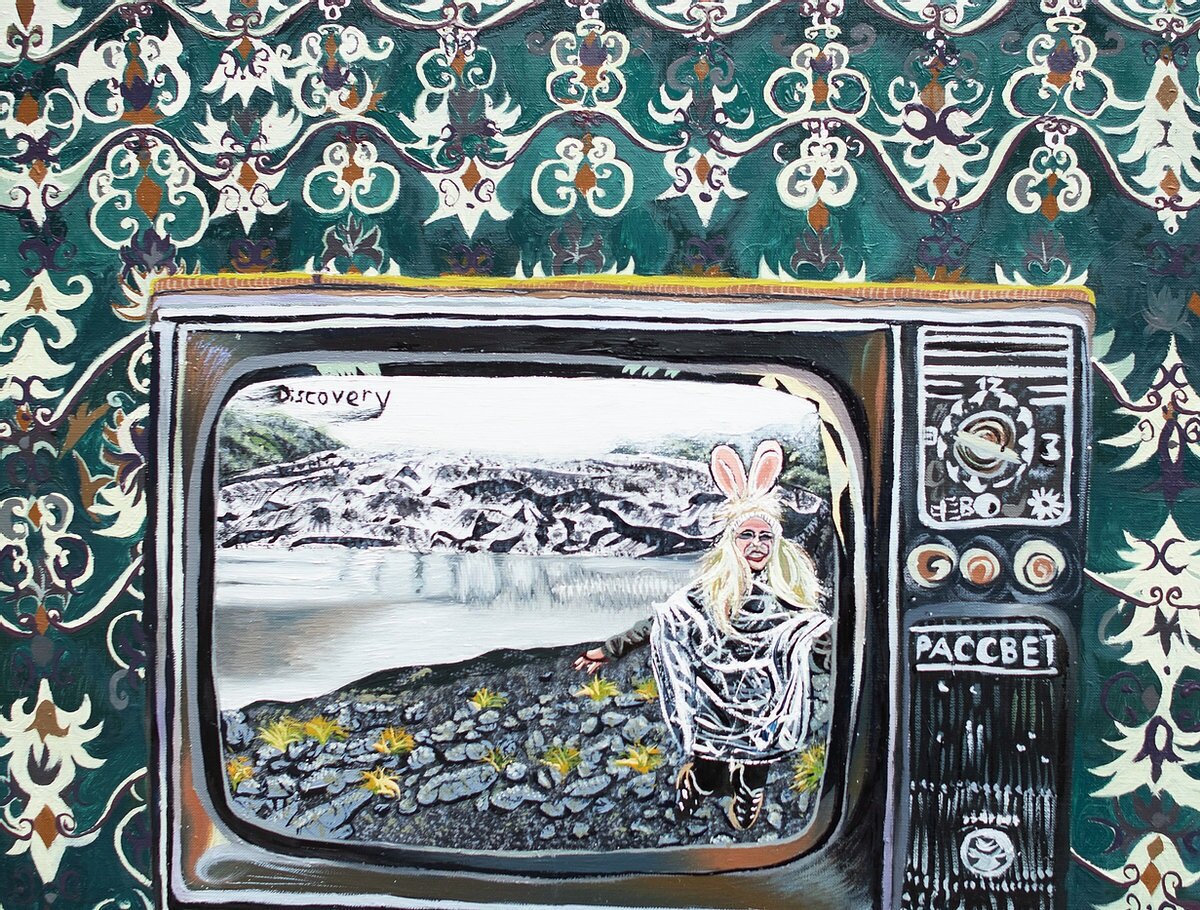

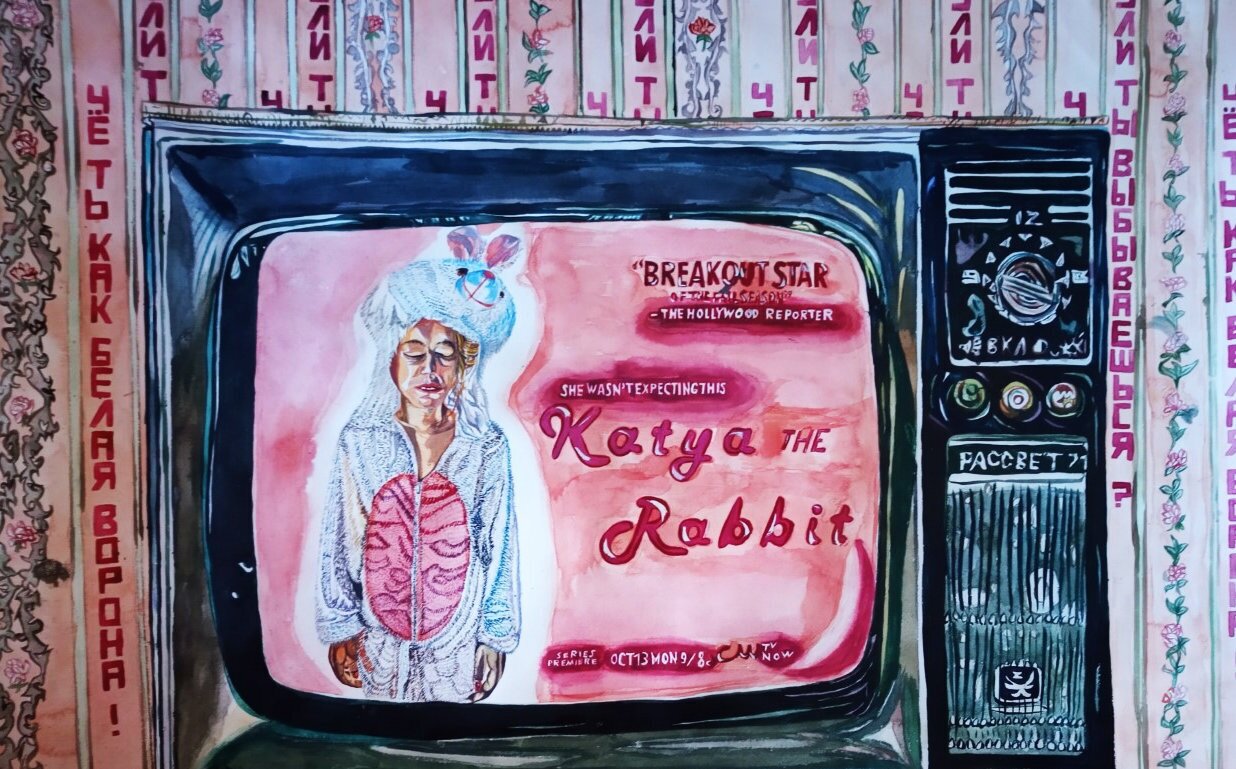

Katya Kan was born in Almaty and grew up in London. Her works are a reflection of her search for a home, memories of her Soviet childhood, and a plunge into the surreal world of eternal celebration with a tinge of melancholy.

Utopian Soviet childhood

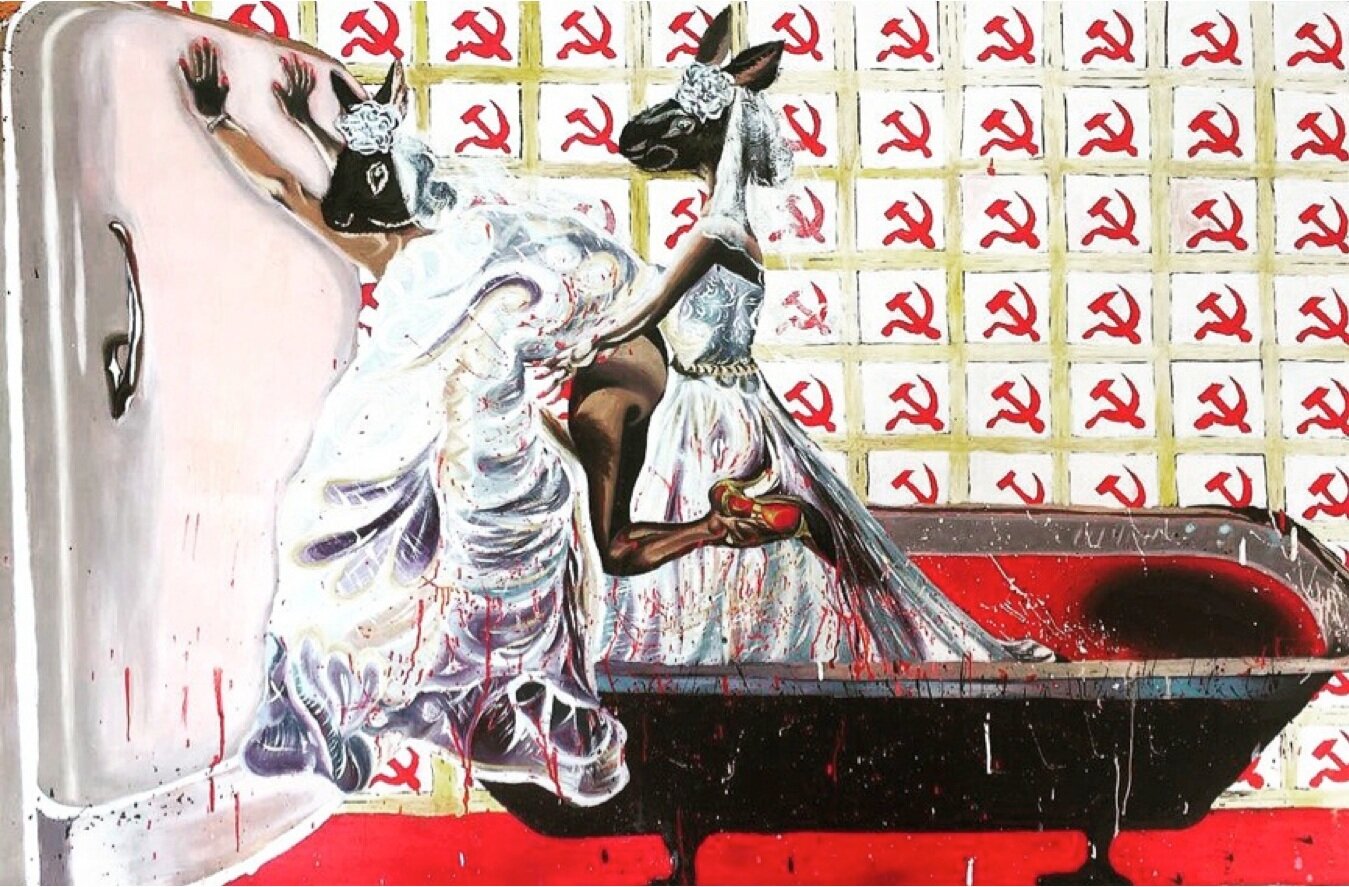

I was born in 1987, at the end of the USSR, and spent my most formative years in Almaty. In my work, I don’t analyze Soviet ideology: for me, that time is associated with the emotional space of childhood and its surreal feeling. The image of the rabbit represents my sense of utopia, a kind of escapism in my memories. Through my creativity, I return to a state, where my experience of life was much more authentic, and my sense of joy and sadness was experienced much more deeply.

The feeling of home

Throughout my entire conscious age, I find myself looking for a home. Many warm memories are connected with my hometown: Alma-Ata, my home and relatives are here, but every time I come back to a completely different place. Before, each visit would depress me with an obsessive comparison of the present and the past, big and small changes that took place without me. For example, when came back to Alma-Ata in 1995 after living in the US, I was extremely upset at seeing my father rearrange the bookshelves and surrounding furniture and would try to rearrange everything from memory.

My father, the writer Alexander Kan, writes in his books that home is not where you live geographically, but rather his passion for literature became home. Perhaps this search for a home has something to do with family lineage for my father belongs to the Korean diaspora in Kazakhstan. His family escaped from North Korea back in the 19th century and then after meeting my grandfather during her chemical research studies in St. Petersburg, my grandmother left him in the 1960s in Pyongyang in search of a better life and more career opportunities in the Soviet Union. Therefore, my father’s reflection on what a spiritual home is and how to find one's inner sense of home has always been an important topic in our conversations with him.

Emancipation and sexuality

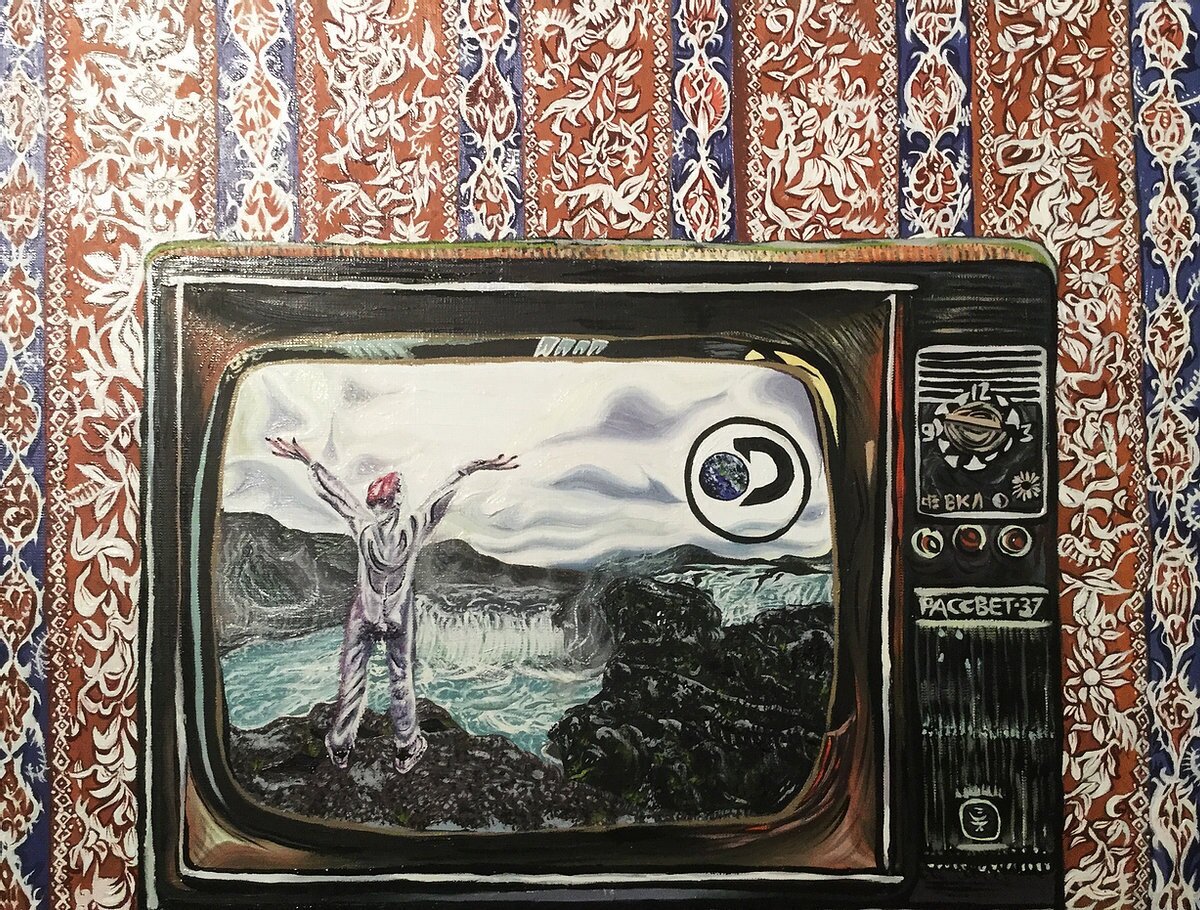

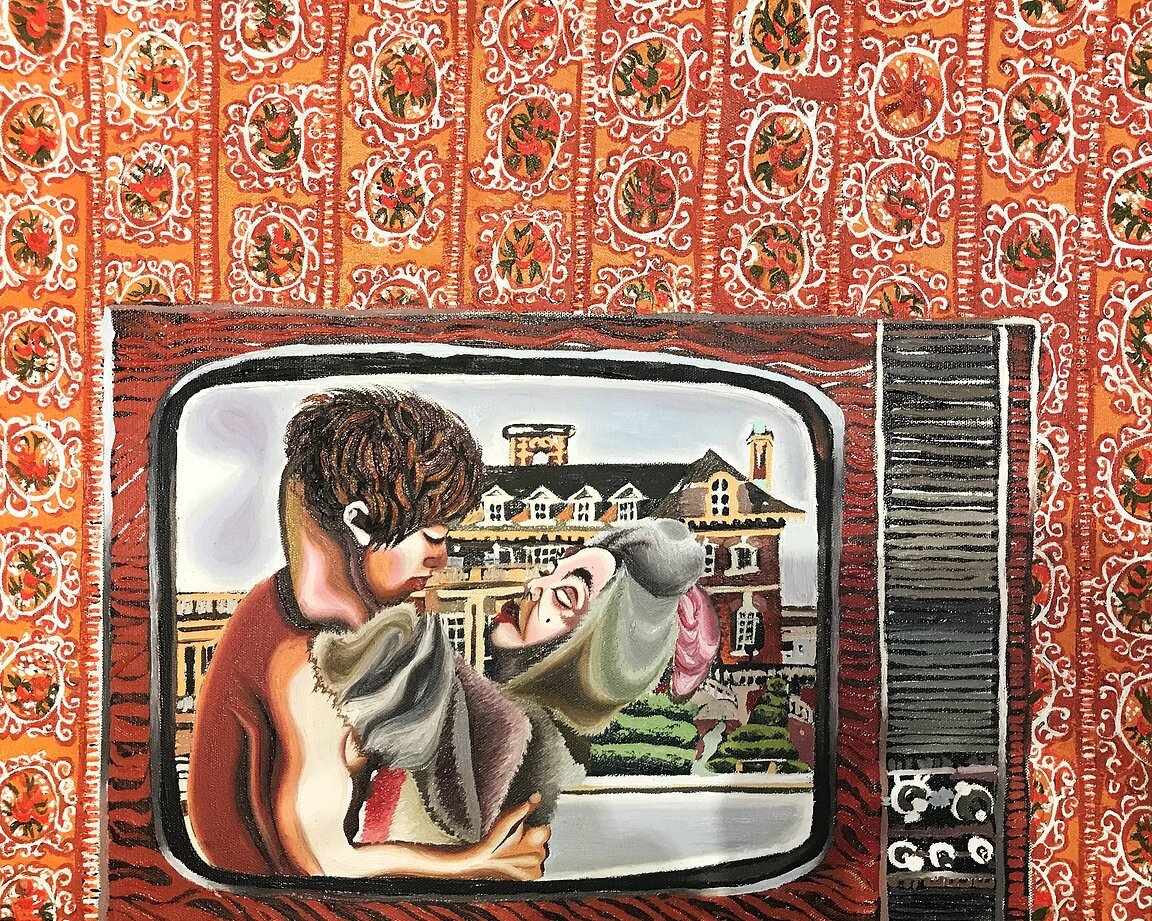

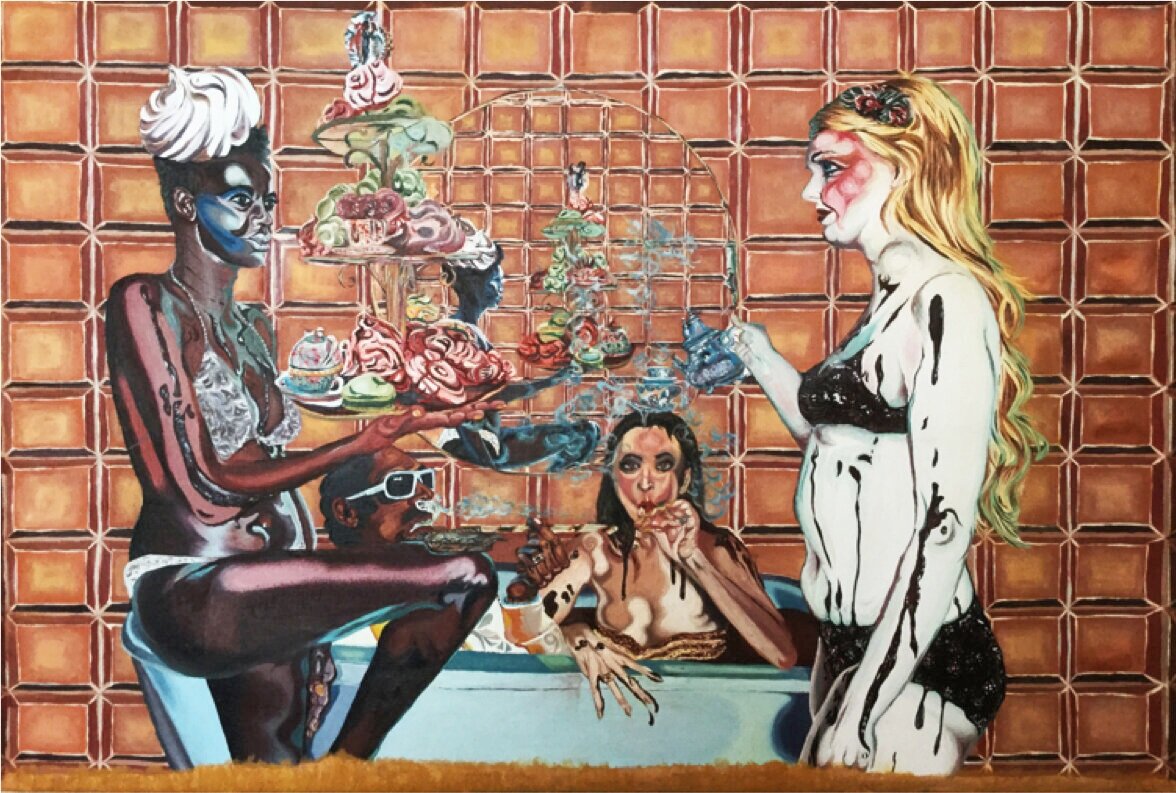

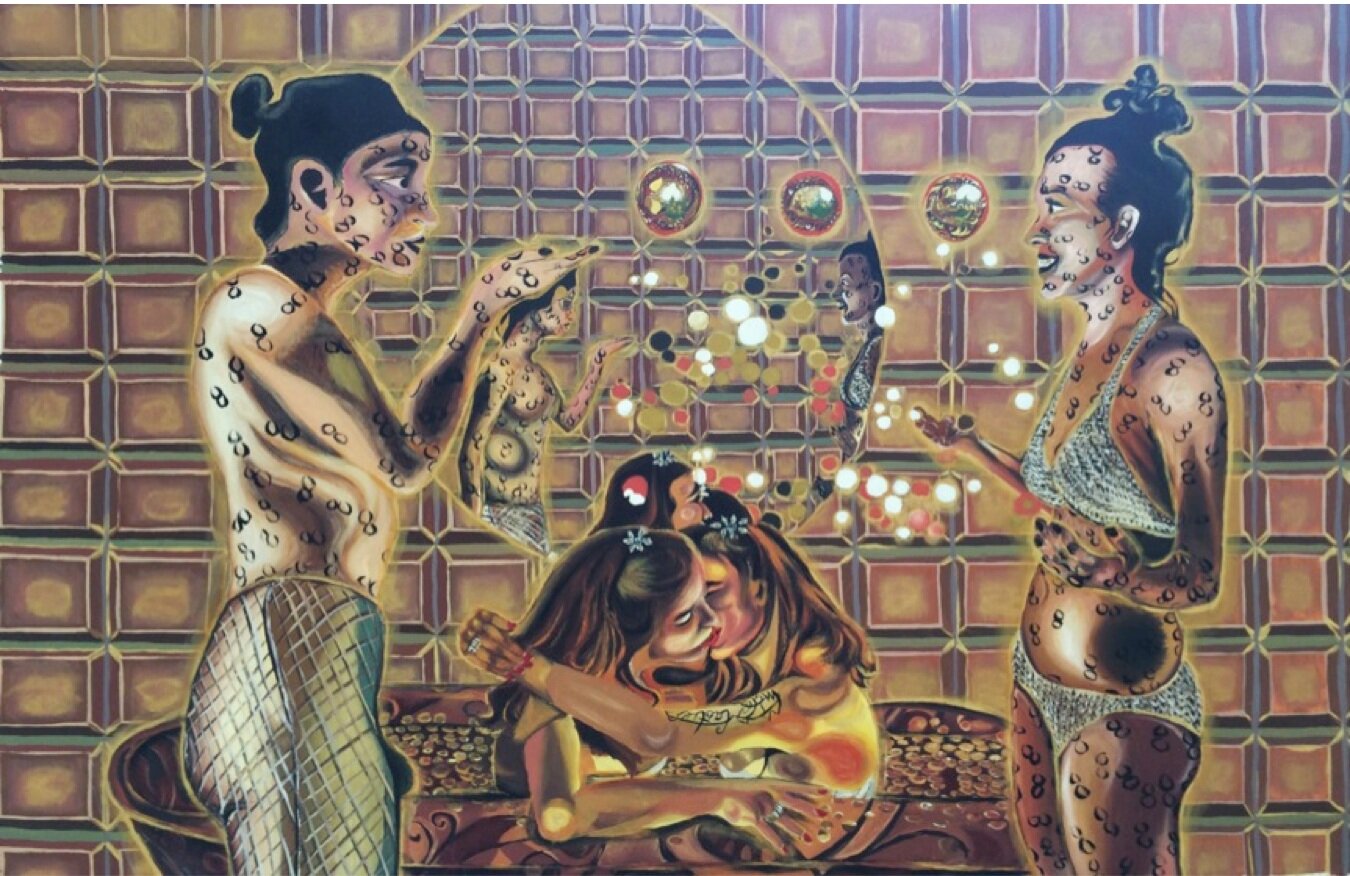

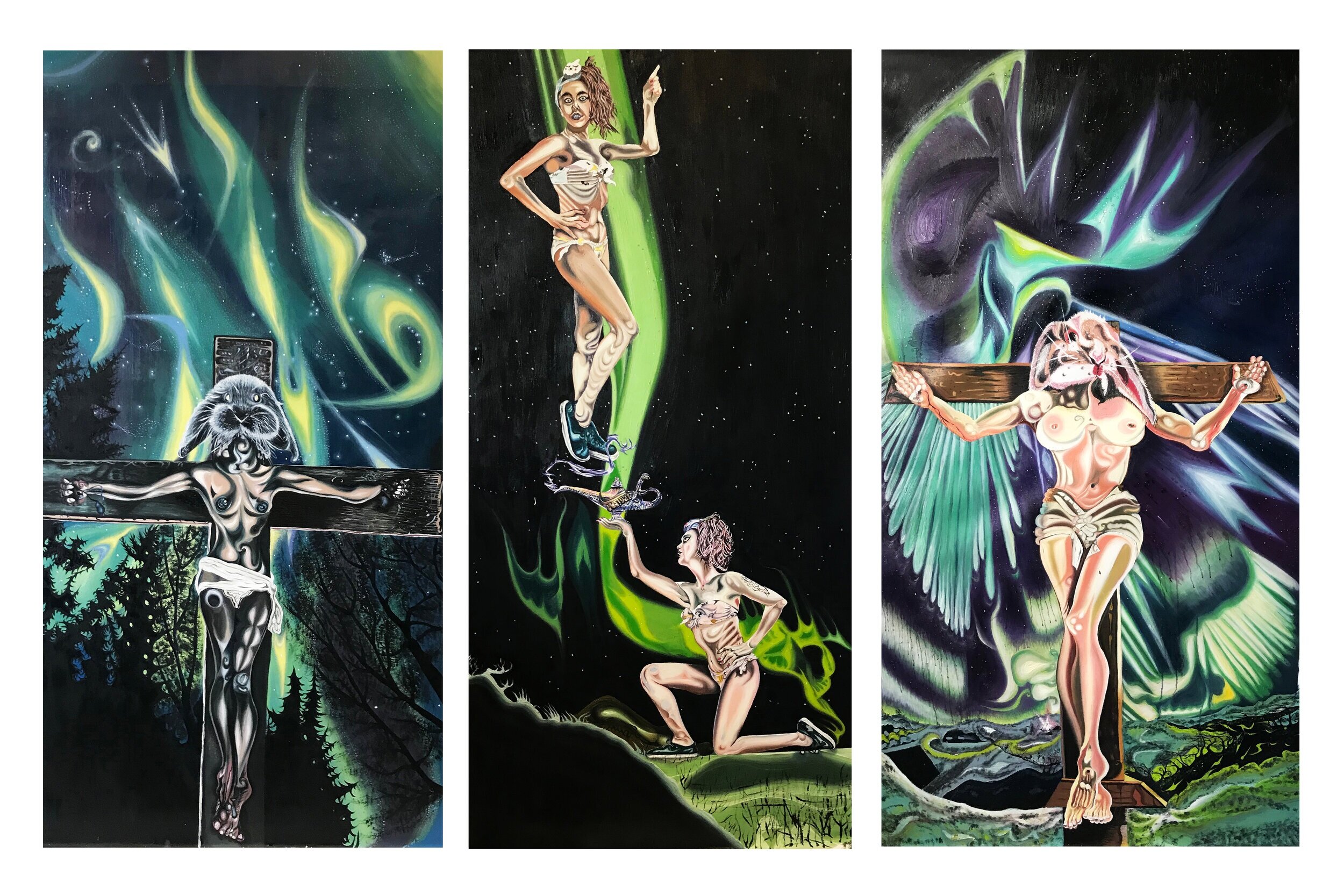

For a long time, I was cut off from a sense of sexuality, or even a sensual experience of my own body. I went to an all-girls school and during that period I inhabited a bubble, I had no emotional contact with anyone. Consequently, in my work, I attempt to rekindle my connection to my own sensuality in order to compensate for the experience that was displaced during my school period. I think that sexuality works even on a more basic level, in other words, the French notion of “jouissance” when you feel pleasure from your body independently of your contact with other human beings. Sexuality in my work manifests itself through Guy Debord’s concept of the “society of the spectacle”, for example, expressed as fetishistic ceremonies: hare orgies, my performance of the scatological act. These forms of spectacles are inspired by my immersion into various subversive environments in London, Paris, and Los Angeles, where I visited various Libertine clubs. With the permission of these swingers’ clubs, I would take photos of threesomes and glory holes, which I would later use for my art pieces. As I consider myself to be a closed person, detached from my own sexuality, I found the sexually emancipated characters, whom I voyeuristically observed here simultaneously mesmerizing and disturbing. I believe that before striving to transcend social and political boundaries, an artist should overcome their inner barriers.

Art as an act of falling in love

In my art, I aspire to express a certain state of being: above all, a pleasant kind of anxiety and the effortlessness of falling in love. I don't like the logocentric trend towards epistemological academia in contemporary art, whereby all artists today must be theorists, to analyze global issues, devoid of one’s subjectivity. Very often, such works don't offer a new view, but rather provide a social commentary on the cliched ideas of academic researchers from other fields. I am interested in love in a universal sense, as an irrational force, a release of serotonin. I am depressed by the traditional Third World hegemonic and patriarchal concept of love in the traditional sense as a banal relationship between a man and a woman. In my view, the feeling of love is much more multifaceted and complex than the banal plots of songs and romantic movies.

Inherent in this conventional portrayal of love is the process of simplification, objectification, people should not build relationships out of some need, fear of being alone. Instead, for me, the journey towards experiencing love is equivalent to opening up one’s channels and chakras to the zero-point energy as well as the intrinsic pure and unclouded consciousness of a child, which we are so quickly losing due to the influence of various social institutions.

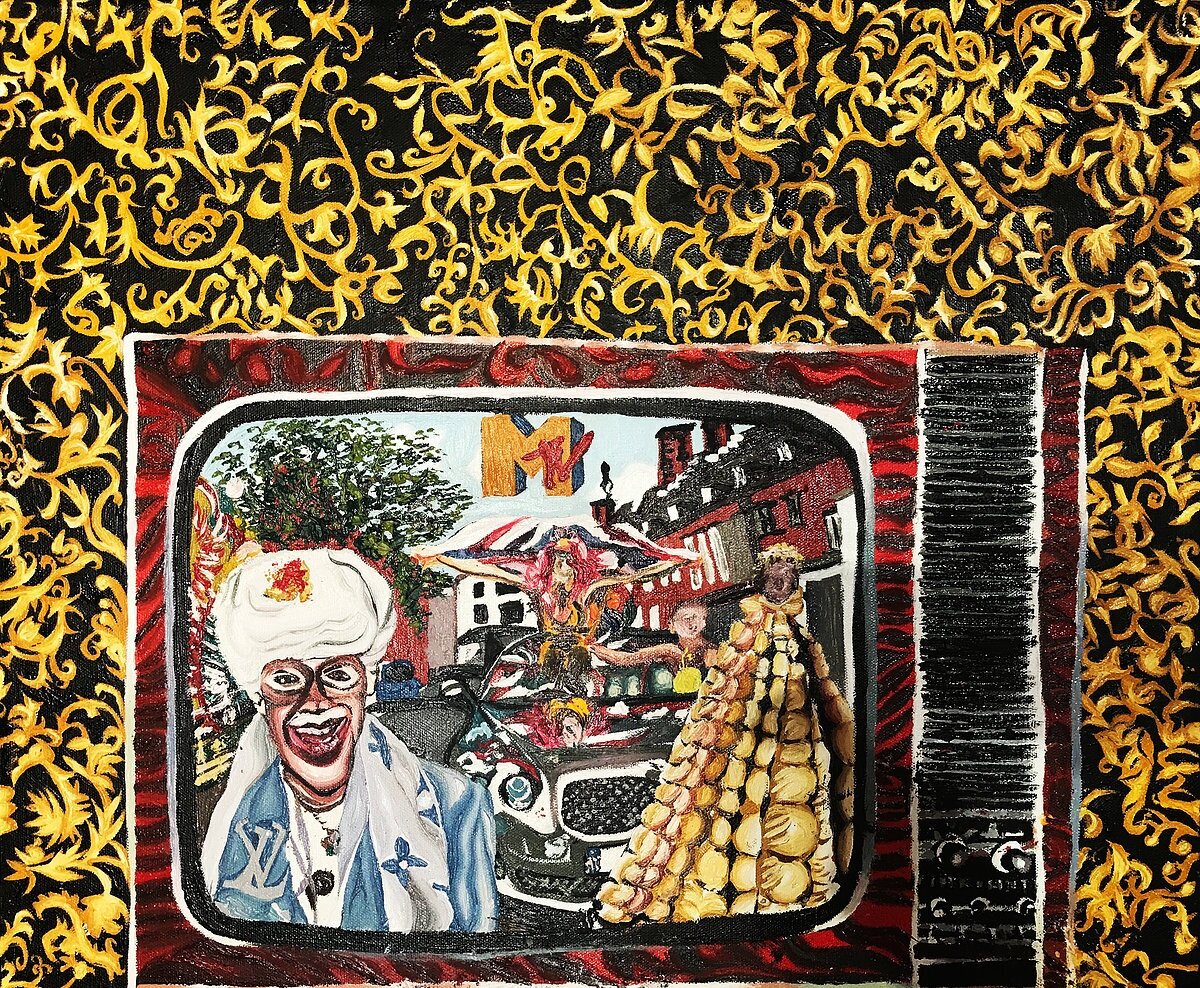

YOUNGER HEART

2019

Écriture féminine

I have never tried to frame my work within any kind of discourse, but the subject of feminism has always concerned me, especially the 1970s movement Écriture féminine, which is perhaps now considered a tad outdated. Its pioneers were Julia Kristeva, Luce Irigaray and Hélène Cixous. I studied this movement during my English Literature with French studies at Edinburgh University. I find this movement much more subtle than the more militant, literal, and crude of their contemporary second-wave American feminists. What interests me even more than women's civil rights is the exploration of a feminine language, previously unexplored by previous generations through one’s biologically defined female corporeality, and, in general, how one’s literary and visual language reflects femininity as a phenomenon. I don't like the more American feminist approach of abandoning one’s femininity in exchange for adopting a male image. Rather this mimetic tendency resembles a simplistic act of mimicry. As an artist, I was shocked to have been confronted with sexual objectification. I used to naively believe that sexual harassment was a relic of the past, especially in the contemporary gallery business. However, one tragicomic incident changed my mind: a gallery owner, who worked for Gallery in Los Angeles, who sent me very indecent and disrespectful messages, apparently taking advantage of his status as a gallery director in order to draw me in. My video art piece, “Bunnytease”, which was screened at various indie film festivals such as MicroActs depicts my playful and ironic reaction to these sexting messages and objectifying sexual fantasies in the form of me dancing with our texting exchange in the background.

Slipping out of binary categories

Although there are many references to queer culture and a queer aesthetic in my artwork, I have evaded falling under different types of categorization. This critical attitude towards repositioning and manipulating one’s identity evolved with a co-partner into a project. More specifically, I created an online persona, which parodies current artistic tendencies, is desperate to exhibit in any art show, however insignificant, on whatever terms, in a gallery for money, on the street, in a garage or in a dusty toilet, undergoing any form of sexual, monetary and/or physical exploitation necessary to achieve this. An obligatory criterion of this cyber persona, is, of course, the exploitation of my North Korean/Russian ethnic identity as a process of deliberate and fetishistic exoticization as a popular device as well as the emphasis on my ambiguous sexual orientation in the contemporary world of art grants and so on. Together with my creative partner, we would write long monologues, beginning with "I am a North Korean lesbian artist,” and ending with “How do I apply to exhibit here?” This performative cyber identity parodies the process of labeling, which many contemporary artists that the art system uses and that so many artists have come to love. As a result, despite referencing the queer aesthetic, which I resonate with, I would never label myself as a queer artist as I would not like to be categorized according to the current trends of identity politics.

The reality of parody

My parody videos constitute a form of self-therapy. In my mind, listening to music and enacting dance choreographies is the fastest way to release one’s instinctive feelings. Even if you consider yourself to be a bad dancer and the pop song you’re playing is vulgar, frivolous, and banal, imagining yourself as a glamorous and self-confident pop star enabled you to feel more alive and liberated and to release a huge burst of spiritual and physical energy. I believe that 21st-century pop culture with bands such as Little Big and rappers like Tyler the Creator and Amine is moving towards a form of self-parody. In the nineties and before that years, pop performers took themselves much more seriously, and treated their self-image much more naively, and took reality at face value. Today, the art world, like pop culture, has become an unalloyed game of identity politics, an anguished kind of self-irony as well as the proliferation of never-ending satirical memes and puns about contemporary society.